“Finding himself through art and using it to heal”

Russell Noganosh set off for Plains Indian Cultural Survival School in his early twenties—but the skills he learned didn’t come from his studies. Noganosh’s life lessons came from friendship and art.

Noganosh enrolled in school after fleeing from a foster home in Ontario where he said he witnessed and experienced abuse.

He decided to attend the Plains Indian Cultural Survival School because he was interested in learning about his culture and language. But it was during his stay at the Calgary-based school that he met Isaac Bignell who became his art mentor and life long friend.

Bignell was an artist who stayed in the same place as Noganosh and his classmates in Calgary. Noganosh said he liked what he was doing and loved art so he gave up school to travel with him.

“Isaac and I hung out, so I left the school and thought maybe it was the road to more teachings. He would show me different techniques and he would say, ‘I’m showing you my different styles, take one of my styles and try it out,’” explained Noganosh.

Noganosh and Bignell travelled all over Canada and through the states selling their paintings.

Noganosh said his work is inspired by nature and his own experiences.

“What inspires me? A walk in the bush, seeing the mountains, being a participant in powwows and ceremonies, stories from elders,” said Noganosh.

But some of his work emerged as part of a healing process. Last year, Noganosh was diagnosed with a rare form of skin cancer and with the help of his partner, Sherri, and his art, he persevered.

“The cancer's been taken out of my body… the greatest gifts on earth have been given to us, and to keep on painting and painting, and I said I’m going to paint through this,” he said.

Noganosh said that while he waited for his diagnosis, he painted and it was humbling. He created a whole series of paintings during his treatment and he said it helped him heal.

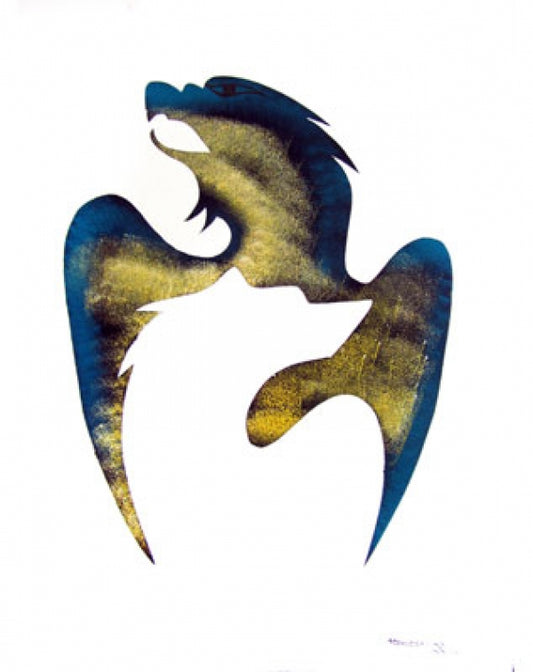

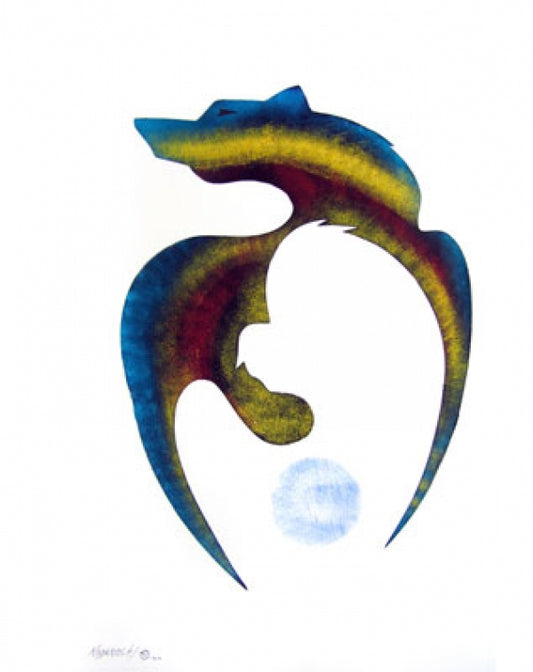

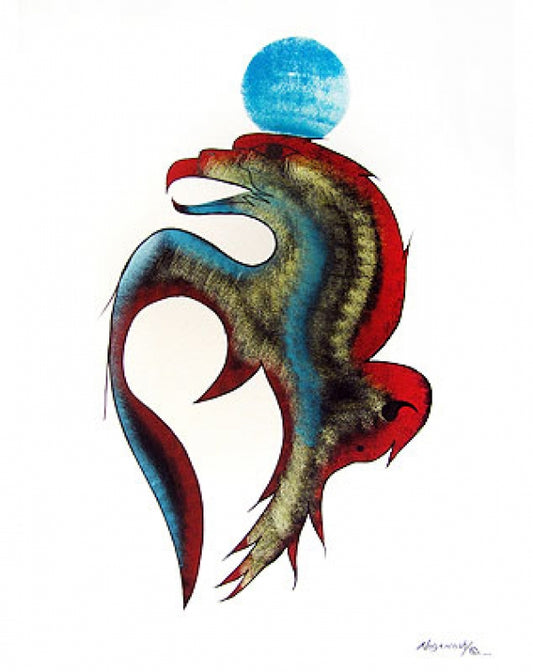

Recently, Noganosh completed three new pieces that portray elements of the universe such as wind, fire, earth and water.

“Water is the most sacred, it keeps people alive. Treat it like your mother or father or children, with respect. I just finished these pieces…I’m pleased with what I’ve been doing, it directs my focus, it takes my mind off the position I was in,” he explained.

Noganosh said in the scariest moments of life, you have to stay positive, have faith and for him, he has to paint.

“Like Bob Marley sending a message through his music, the way I look at it is sending a message through my art. Take care of the water take care of the land take, care of your children, grandchildren and their children,” he said.

Noganosh said he didn’t grow up with that nurturing and so he expresses his experiences and feelings in his work.

“I had one painting that I did awhile back of Children’s Aid coming and picking up kids; my brother and I, and I painted that picture, that was the story I was told so I painted it," he said. "I put that logo…CAS on the side of a 50’s car that would drive up to the reserve and apprehend children."

The artist shared that after crying and sharing, he painted black over top of the painting and he painted a healthier picture with richer colours.

“Do what you feel and put your heart into it,” he said of the painting and healing process.

Before Noganosh discovered his love of painting, however, he sculpted and carved stone.

He started sculpting as a teen, but he didn’t consider himself a serious sculptor until later in life. A relative taught him the art of sculpting and he created transmetamorphosis pieces—transporting art from stone to a painting, or a painting to stone.

“I mutated the carving of a fish. I turned stone into a two-headed fish and then the tail of the fish was a four-point deer antler, and you know the gills—I took two horns from the antler and put it on the side of the fish and then underneath the fish’s chin, I put a turtle shell. I put stone for eyes, stones for a big long mouth and horsehair,” he said.

Noganosh described the two-headed fish as contemporary and environmentally aware.

“You have to come with your own style,” said Noganosh.