Collection: Gloria Escoffery

Gloria Escoffery was an important Jamaican artist, poet, teacher, art critic and journalist. Her work as an artist and writer evolved as part of the burgeoning Jamaican art movement of the 1940s and 50s. Later she became - partly, but not completely, by choice - somewhat of an outsider but retained her creativity, proud to call herself "something of a rootswoman".

For more than half a century she produced intellectually demanding literary and visual work. Full of social satire, symbolism and mythology, her more recent work, in particular, was a celebration of the "rootsmen", the self-taught, rural artists of her beloved island.

Escoffery came from the Jamaican professional class and was trained as a classical artist, but her work reflected rural life and was expressive of Jamaican folk culture. Indeed, her collection of wood carvings by her friend Brother Everald Brown, perhaps Jamaica's leading intuitive artist and a self- ordained minister of the Ethiopian Orthodox church, and his son Joseph, held the inspiration for much of her important later work. These carvings were reborn - like nursery animals coming alive at night - as a cast of richly tragi-comical characters in her illustrated and privately published book of poetry, Rootsman Adam Reincarnates For The Millennium (2000). It deserved a larger audience.

The work is typical Escoffery: a sure hand, wise and humorous, calling on all the traditions that made her such an invigorating and inquiring artist. Always critical of her society, she was never aloof from it - even if she sometimes felt excluded by ethnic origin and education, and then by distance from the Kingston-based art and literary establishment.

The youngest of three children, she was born in Gayle, in the agricultural parish of St Mary, but spent most of her childhood in Brown's Town, a market community inland from Jamaica's glittery north coast. Her doctor father was descended from white Haitians who had fled its revolution. Her mother's family were English and Jewish Jamaican. She was educated at St Hilda's High School, Brown's Town, and in 1942 won the "island scholarship" and went to McGill University in Montreal, Canada.

She returned, at a time of political and artistic stirrings, and she was invited by Edna Manley, wife of Norman Manley, leader of the People's National Party and future post-independence prime minister, to become literary editor of the PNP's weekly, Public Opinion. She also designed sets for Jamaica's Little Theatre.

From 1950 to 1952 she studied at London's Slade School of Art where Lucian Freud taught and where Unity Spencer, daughter of Stanley, was a student. When Edna Manley, who became a close friend, visited Escoffery's studio on the latter's return to Jamaica, she commented: "You really are an artist, not just a journalist."

At first, in works such as Banana Plantation Workers (1953), she identified with Jamaica's early nationalist realists. Classical in composition, these paintings drew on Cézanne and Poussin, according to David Boxer, emeritus director of the National Gallery of Jamaica, who always promoted her work. He included her superbly composed acrylic, The Old Woman (1955), in Jamaican Art 1922-82, the landmark exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC.

Later, her work became more experimental, dreamlike and at times surreal, full of literary allusion and often incorporating decorative friezes. One of her most ambitious works, dating from the 1980s, was Mirage, on five panels, celebrating her love for the land, in this case the desert landscape of the Middle East - a tribute to her Jewish grandmother - turned into a battlefield for cultural dominance.

She had left Kingston in the late 1950s and moved to Rio Bueno where she painted, ran an art gallery and taught in local schools. In 1967, she adopted her son, Fabian, before returning to Brown's Town where she was to live for the rest of her life, in a cottage and studio, in the grounds of her old family home. There, from 1975 she taught English literature to sixth formers at the Brown's Town community college, having gained a teacher's diploma at the University of the West Indies. It was the start of a richly creative period: apart from painting, poetry and teaching, she wrote for the Jamaica Journal and had a weekly column in the Gleaner newspaper. She retired from teaching in 1985.

Sometimes her immensely long, engrossing letters expressed a sense of intellectual isolation, but never of despair. They often contained vivid descriptions of mishaps. On one trip to Kingston, her portfolio, stuffed with illustrations for a children's book, was left on top of her car. When the car drove away, the portfolio fell off and was lost. But her energy and imagination meant that there was always more creativity to come. In the last few years, she had become enthralled by the computer: drawing with the mouse and creating layouts for her poems. It offered a new way to design - always one of her passions.

There were two published collections of poems: Mother Jackson Murders The Moon (1998), and Loggerhead (1988). The latter was dedicated to, among others, David Boxer and Edna Manley. Escoffery wrote that these were friends who saw that "I was waving, not drowning, and waved back." Courageous, determined, outspoken, "Miss G", as she called herself, raged against what she saw as the apathy of Jamaican society (though few could match her energy) and its violence (she launched a campaign against corporal punishment in schools).

In her last years, she also wrote a blueprint for the development of Brown's Town. Her public spiritedness, generosity and vision is perhaps best encapsulated in the dreams she had for a Brown's Town cultural centre, based around her library of 1,000 art books, in the grounds of her home.

-

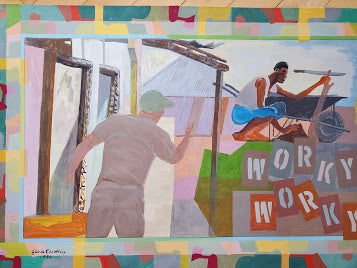

Worky Worky

Regular price $4,995Regular priceUnit price / per$0Sale price $4,995